The journey from hostility to hospitality - a reflection

Finding a place in our hearts for others.

In this reflection based on the writings of Henri Nouwen, having considered the journey from loneliness to solitude, we turn to what Nouwen calls the second characteristic of the spiritual life - the movement from hostility to hospitality.

Fr. Simon

Some years ago, Fr. Michael Czerny, the Vatican undersecretary for Migrants and Refugees persuaded the Canadian sculptor Timothy Schmalz to create a sculpture highlighting the plight of refugees. The result was 'Angels Unawares', a bronze, life sized sculpture depicting a group of migrants and refugees from different racial and cultural backgrounds and from diverse historical times. It was unveiled by Pope Francis on 29th September last year. These people stand shoulder to shoulder, huddled together on a makeshift raft. From within this crowd, an angel's wings emerge, suggesting the presence of the sacred among them. The inspiration is taken from the New Testament passage:

'Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels, unawares' (Hebrews 13:2).

Welcoming strangers

As a parish we benefitted greatly by showing hospitality recently. We were blessed to welcome among us for a few months the diocesan seminarian Yemane Aradom. Yemane's story touched many hearts. It is a story of courage, faith and resilience. During his travels to our country, like many refugees, Yemane clearly experienced much hostility. Perhaps some refugees and asylum seekers still experience such hostility on our streets now, though they have apparently reached a place of sanctuary? Thankfully, before he returned to seminary, Yemane was able to talk about the tremendous sense of hospitality that he had experienced during his time with us and we certainly benefitted infinitely from getting to know him, our lives being enhanced by his wisdom and care.

When considering the injustice done to those seeking sanctuary, it seems that the cruel side of human nature is often demonstrated in its most vivid form towards the stranger. The scriptures often reflect the hospitality of the human spirit - evidenced in Abraham's welcome of the three strangers by the oak of Mamre, the story of the prodigal son, in the many people who took Christ into their home and in the story of Emmaus, pictured above. But there are stories, too, of the hostility shown by individuals and societies towards others. The people of Sodom and Gomorrah were particularly noted for their hostility to the stranger, to the extent that God's retribution was called down upon them. They were unable or unwilling to see God in others who were from outside their locale - simply treating them with violence and derision. Many years later, the mood of the people surrounding Jesus would turn hostile in a moment. People from His own town took him to the brow of a hill intending to throw him off, the Pharisees were constantly watchful in order that they might entrap Him, the crowds who welcomed Him into Jerusalem with waving palms would soon turn against Him and, indeed, He was deserted by His own friends at a time when He needed them the most. It was at the peak of such hostility that His Passion began.

Since the early days of the current pandemic, we have seen reports of contrasting examples of hostility and hospitality from within our own society - one now fuelled more than ever by anxiety and fear. Heartwarming stories have reached us of those who put themselves at risk for others, those who care for the sick no matter that they put themselves in danger by doing so, those who bring a smile to faces in troubled times, those who ensure the needs of the most vulnerable are met, of food-banks being provided for and giving to those in need. Many individual acts of kindness and hospitality take place daily, often unnoticed. Conversely, there have been a few instances of civil disobedience, selfishness and anti social behaviour. So we see hostility and hospitality played out on the stage of the world around us every day.

A 1951 film entitled 'When Worlds Collide' envisaged the destruction of earth by a rogue star. When we come into contact with others, then worlds collide. Our life is a whole world in itself. A world of experience, faith, opinion, love, sacrifice, weakness and pain. So too are the lives of the people we meet on our journey through life. When we encounter them at work, in the street, at a party or a parish function, our worlds collide. If either or both are hostile for some reason, then the encounter can be destructive rather than life enhancing. However, if we cultivate a spirit of hospitality which we offer even when we are feeling threatened or fragile, then that colliding of worlds can become a tremendous, life giving experience for both parties involved.

Entwined in the very fabric of our faith is the call to provide a hospitable space in which strangers can become friends. This takes a humble spirit - we must be prepared to offer the hand of friendship and make sacrifices, even if our kindness is likely to be rejected. Pride can get in the way, particularly when we are feeling defensive or under attack. Pride leads to stubborn hearts which, in turn, lead us down a path rejected by Christ himself - that of being kind only to those who are kind to us:

"If you do good to those who are good to you, what credit is it to you? Even sinners do that." Luke 6:33

A stranger, of course, like the biblical term 'neighbour' is anyone whom we might encounter in the course of our life but who was not previously known to us. Nouwen takes the understanding of the word further. He sees the stranger as the person who may be estranged 'from their past, their culture, their country, from their neighbours, friends and family, from their deepest self and from their God'. If this be an accurate interpretation of the word 'stranger' then we have our work cut out! A rise in personal and family dysfunction over the past few decades has led to many people leading fearful and lonely lives in which contacts are plentiful but a good friend is hard to find. The distractions of the world mean that we are seldom bored and this has, perhaps, led to a fall in creativity. We might apply this impoverishment of creativity to our relationships too. Why work on a friendship when there are literally thousands of people waiting 'online' for us to turn to?

The drive to increase efficiency in recent times has also led many to live lives which are no longer open to the spontaneous encounter. Neighbours and friends rarely call unannounced, get togethers have to be planned some time in advance, often many weeks before. The tendency to communicate by text and email may have blunted the human knack for interpreting non-verbal communication and relationships often collapse because of a poorly thought out text or a hurried phone conversation.

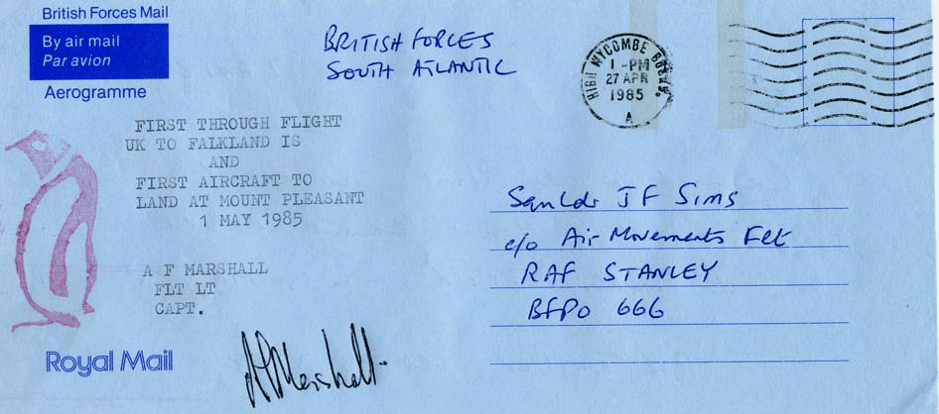

As Chaplain to Naval warships I witnessed a gradual change in the way that sailors conducted their relationship with loved ones from afar.

In the mid-nineties, when sheltering in some foreign port, the ship's office would post off and collect from the local agent a host of 'blueys' - letters written on thin blue paper which formed into an envelope and could be sent home for free. Families would communicate with their loved ones at sea likewise. Hours would be spent pouring hearts out in what now seems to be the lost art of letter writing. Sometimes, letters written in haste and then regretted later would be 'stolen back' from the ship's office before they could be posted and a more appropriate missive would be penned in time for the next post, thereby avoiding a relationship disaster! Not so with emails - once the little button with a flying envelope on it was clicked, there was no taking it back. The result was an uplift in marital woes, relationship problems and a ship's company more pre-occupied than ever with the ongoing sagas of home. Technology had brought our families and their issues much closer to the ship, be it in the South Atlantic or the Indian Ocean, and whilst this had it's advantages, it certainly brought its problems too.

Hospitality is expressed through words as well as actions. How a person reacts when we begin to open up to them will determine how deeply we share our thoughts and concerns. If they take every opportunity to turn the conversation back to them, if they fail to pick up on the distress signals we are sending out or if they clearly lack the ability to empathise, then we are likely to look elsewhere for solace. It's a useful exercise to examine how hospitable we are to others in regular conversation with them. Are we sensitive to those distress signals? Are we prepared to put our own needs to one side when another person is seeking our counsel? Can we, as the native Americans say, 'walk a mile in another person's moccasins'? And then the next question is how do we transfer those skills formerly exercised in person or in letter writing to the world of texting, email and social media? How do we create through modern communication what Nouwen calls a 'place where lives can be lived without fear and community can be found'?

Part of the answer lies, perhaps, in being prepared to buck the trend. To 'phone a person if we are worried about them or to call round and see them rather than simply sending them a quick text. If our worlds need to collide in order for true hospitality to be given and received then it's no use relying simply on a satellite signal in space!

There isn't a person in the world unfamiliar with the damage that hostility can do to our sense of mission and purpose in life. Often, that hostility can emanate from people close to us, friends, colleagues or family from whom we might normally expect support. Doctors, priests, lawyers, social workers, psychologists and counsellors who start their work with a great desire to be of service will often find themselves victimised by intense rivalries in their own personal and professional circles. Ministers and priests who announce peace and love from the pulpit often experience it as hard to find in their own cohort. Many social workers trying to heal family conflicts struggle with their own at home. Perhaps the phrase 'charity begins at home' might prompt us to spend more time ensuring peace and tranquility in our own lives as well as in the lives of those to whom we relate professionally?

Getting back to the idea of hospitality being about creating a free and friendly space, Nouwen likes the German word

Gastfreundschaft

which means friendship for the guest. The Dutch use the word

gastvrijheid

which means freedom of the guest, perhaps reflecting the Dutch race's great respect for freedom of expression. Either way, both nationalities clearly see a hospitable place as one where the guest can feel 'at home'. False hospitality is where someone offers refreshment and rest which comes at a cost - often involving indoctrinating us with their own ideas. True hospitality creates not a place in which people can be changed, but rather a place in which change can take place. It involves providing a place free from dividing lines and judgemental behaviour.

Every Monday afternoon in my first year of seminary I used to visit an elderly widow as part of the pastoral programme. Mrs Wilkinson lived in the small mining village of Langley Park which lies in a valley behind Ushaw College near Durham. I would descend the hill

into a village filled with the smoke of coal fires - retired miners and their widows seemed to be given free coal for life. There, I would enjoy a hospitable afternoon in the home of a woman whose Methodist upbringing brought insights I'd never experienced before in my Catholic world. By the glowing fire, over tea and home made cakes we would talk about many things. One phrase I remember Mrs Wilkinson using often was 'you must never take somebody's song away'. It gave the lovely image of those around us being songbirds and it being our task in life to help them sing their song. A space of hospitality is a place to help people sing their song, give expression to their passions in life. It is not a place to make others think like us. Thoreau puts it well:

I would not have anyone adopt my mode of living on any account; for, beside that before he has learned it I may have found another for myself, I desire that there may be as many differing persons in the world as possible; but I would have each one be very careful to find out and pursue his own way, and not his father's, mother’s or neighbour's instead.

It was almost as if he were ushering in this new age which truly values diversity.

So, hospitality is love in action. It has more to do with the resources of a generous heart than with the provision of food and space and this takes many forms. Dr. Ron Mulroy speaks in another reflection on this website about writing to each of his grandchildren. That's a creation of hospitality, something reflected in different ways by families across the nation as they seek to let each other know they are special. Teachers spend their lives creating hospitable spaces for children to discover their strengths, so opening up pathways to the future. Parish communities provide opportunities for people to discover different aspects of faith in a safe and friendly environment where no one way of praying is better than another. Good friends provide space and time for us to recharge our batteries and look with fresh eyes on our progress through life so far.

In conclusion, can we use this time of lockdown to improve our ability to offer hospitality in all its different guises to others? Nan-in was a Japanese master during the Meiji era of the late 19th century. He received a university professor one day, a man who had come to inquire about Zen. Nan-in served tea. He poured his visitor's cup full, and then kept pouring. The professor watched the overflow until he could no longer restrain himself. 'It is overfull. No more will go in!' 'Like this cup', Nan-in said, 'you are full of your opinions and speculations. How can I show you Zen unless you first empty your cup?'

Whilst the lockdown period has been frantic for many working from home and, of course, for those caring for others on the frontline of the NHS, for many of us it has provided time for reflection which, if used wisely, will help us to more closely resemble the person God has designed us to be. Perhaps this time is one in which the tea has stopped pouring and, for the first time in many years, the cup is not overfull. So we might feel able to take a breath and pay attention to things we have neglected for a while. In this way, as we improve in our efforts to offer hospitality to those around us, we might just catch a fleeting glimpse of a pair of golden wings and know that we are, indeed, 'entertaining angels unaware'.