The Letter of Paul to the Philippians

St Paul’s letter to the church of Philippi is best known for its passage on the ‘emptying’ of Christ, but it is also a source of pastoral advice and joyful encouragement to the Philippian Christians. Peter Edmonds SJ explores the context and content of one of Paul’s shortest but most appealing epistles.

Hidden in the New Testament among the thirteen letters attributed to Paul is the letter he wrote to the church of Philippi. It is short, only about four pages in a modern translation, but for many it is the most attractive of his letters, because of its positive picture of Paul, his appreciation of the qualities of the Christian community in Philippi which he was addressing, and the pastoral directives that he offers for the sort of problems that arise in any committed group of people who try to follow Christ.

Paul wrote in unusual circumstances. He was in no quiet study dictating to some secretary, but in prison where the prospect was either execution or release. Yet he was a cheerful prisoner. He had no worries for himself. If he was to be put to death, then he would be with Christ. If he was to be released, then he would be free to continue his evangelical work with the church of Philippi. He tells us all this, and more, at the beginning of his letter (1:19-24). He forgets what lies behind and strains forward to what lies ahead, the heavenly call of God in Jesus Christ (3:13-14). Meanwhile, as he writes at the end of the letter, whether he had plenty or was in need, whether well-fed or going hungry, he was content (4:11-12). This sort of language resembles that of the Stoic philosophers of his time, but the difference between Paul and the Stoics was Christ. The Stoics depended on their own resources. But for Paul, ‘living was Christ’ (1:21); he could ‘do all things through him who strengthens him’, namely Christ (4:13). As long as this Christ continued to be proclaimed, then he would rejoice, and he would continue to rejoice (1:18). The reader of the letter soon realises how much Christ means to Paul by noting how frequently the word occurs, three times for example in the first two verses and twice in the last three (1:1-3; 4:21-23).

The people to whom he was writing inhabited a city in the north of modern Greece. Though situated in Greece, it was a city with a very Roman atmosphere. Many of those who lived there enjoyed the privileges of Roman citizenship, and it was a place where former soldiers of the Roman legions settled. It is probably no accident that Paul emphasised the Roman circumstances of his imprisonment. He mentions the imperial guard in describing his imprisonment (1:13) and the ‘household of Caesar’ in his conclusion (4:22). Many think his prison was in Rome itself. However, the distance between Philippi and Rome was surely too great to permit the easy communication implied in this letter, so it is more likely that he was writing from Caesarea, the Palestinian city where the Roman governor had his headquarters. We know from the Acts of the Apostles that Paul was imprisoned there (Acts 23:35). Other experts prefer Ephesus as the scene of his imprisonment, although the evidence for this is weaker.

Paul spoke in generous terms of the Philippian Christians. They were people whom he loved and longed for, his joy and his crown (4:1). He wanted this love to overflow more and more with knowledge and full insight, so that in the day of the Lord they might be pure and blameless (1:9-10). So why did Paul write this letter? In general terms, he wrote for the same reason that he wrote his other letters: to build up the faith of his converts, to remind them of his ways in Christ Jesus (1 Corinthians 4:17). A letter was a substitute for a personal visit, or for the visit of one of his assistants like Timothy or Titus. Such visits were needed to deal with problems that were inevitable with recent converts in Philippi as elsewhere. They were young in their Christian commitment and they needed help and even warnings about the dangers they ran of infidelity and sinfulness in their enthusiasm for a new faith.

It is at the beginning of the second chapter of the letter that Paul makes a blunt reference to certain deficiencies that had come to light in their lives together. We meet new terms like ‘selfish ambition’, ‘conceit’, ‘own interest’ (2:3-4). Obviously arrogance and pride were spoiling the atmosphere of their common life; they were no longer of the same mind, having the same love (2: 2). Later on, Paul will name some of those who were at odds with each other; they were two women called Euodia and Syntyche (4:2).

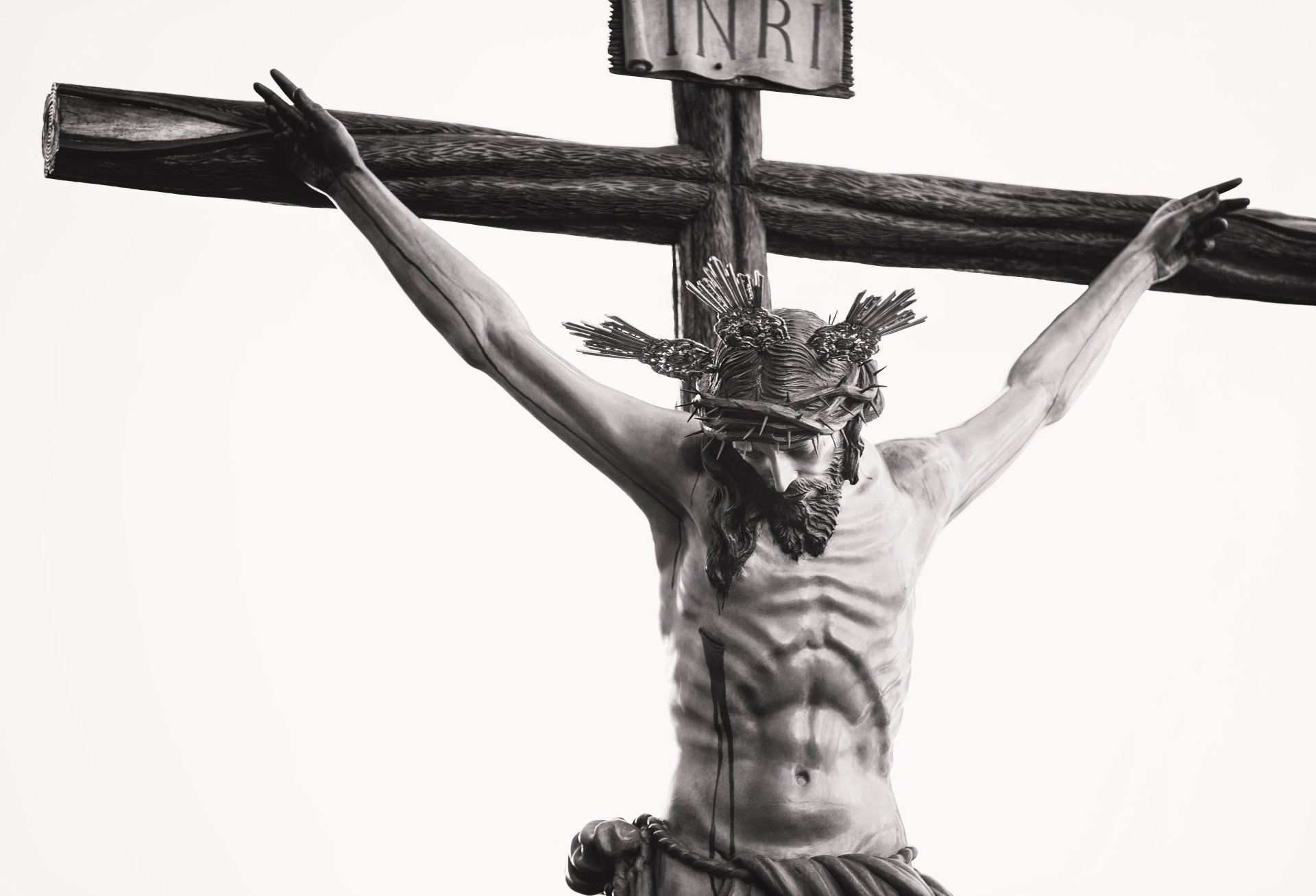

In general, Paul found answers to the pastoral problems in his communities through theology and through Christ in particular. He finds an answer to the arrogance and disunity in Philippi by an appeal to the career of Christ. The six verses in which he describes this are the verses from Philippians most familiar to the practising Catholic, since they are read out every Palm Sunday in the Catholic liturgy of the day (2:6-11). They are often referred to as the ‘kenosis hymn’. Kenosis is the Greek word which means ‘emptying’, and the emptying with which we are concerned here is the emptying of Christ; not just in his incarnation as the Son of God in refusing to hold on to his divine status, but, in obedience, accepting the human condition and dying the death of a slave in enduring the cross of the crucifixion. This is the content of the first half of the ‘hymn’; the three verses of the second half describe God’s response. Because of his impoverishment in his earthly life, God raised him up, gave him a name above every other name, so that he now receives the worship of every creature whether found on earth, below it or above it. Paul applies to the exalted Christ the titles given to God by the prophet Isaiah centuries before (Isaiah 45:23). This then was the Christ to whom the Philippians bent their knees in worship, and if only they would allow this truth to control their heart and being, the arrogance, pride, conceit and quarrelsomeness that was rotting the Christian community in Philippi would find no root among them. In Philippians, Paul is offering a much more colourful and poetic version of the gospel which he had received and passed on to the Corinthians, namely that ‘Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures’ (1 Corinthians 15:3-5).

This passage about the downward and upward paths that marked the career of Christ is the part of Philippians that the Church has made much use of in her liturgy, but it was just one part of Paul’s pastoral strategy for dealing with the deficiencies of the Philippi community. Paul wrote to the Corinthians, ‘Be imitators of me as I am of Christ’ (1 Corinthians 11:1) and he repeats this in this letter, ‘Join in imitating me’ (3:17). In the third chapter, Paul shows how his own life history was an imitation of that of Christ in its downward and upward path. He lists his credentials as a member of the people of Israel. He was a Jew, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews, as to righteousness under the law, blameless (3:5-6). But he had come to regard all this as loss because of the surpassing value of knowing Christ Jesus his Lord (3:8). He went as far as describing it all as rubbish. It was as if he had been in a race in pursuit of Christians whom he believed were betraying their heritage as members of Israel, but he had been pursued and captured by Christ. His only ambition now was to know Christ and the power of his resurrection (3:10). If his Philippian converts had the mind of Paul as well as that of Christ, they could not think of doing anything from selfish ambition (2:3).

This passage about Paul’s own life history is read on the 5th Sunday of Lent in the third year of the Sunday lectionary cycle. Paul offers two more examples of people who have shared the downward and upward path of Christ in this letter, which are never proclaimed on a Sunday. The first is Timothy. He was one of Paul’s pastoral assistants, a co-author of the letter (1:1). He had sent him as his delegate to Thessalonica (1 Thessalonians 3:2) and to Corinth (1 Corinthians 4:17). He had, like a son accompanying his father, ‘slaved’ with Paul in the service of the gospel (2:22). Christ ‘emptied himself, taking the form of a slave’ (2:7). The second example is Epaphroditus who is mentioned only in this letter. He was a go-between between Paul and the Philippians (4:18). His kenosis, his emptying, had come about through the sickness which had almost killed him, but thankfully he had recovered, so that he could continue to serve the needs of the gospel. ‘He came close to death for the work of Christ’ (2:25-30).

But the letter is more than a treatise dealing with a single issue. We may pick out at least two other matters to which Paul directs his attention, perhaps less smoothly than he might have, so much so that some scholarly opinion sees the letter in its present form as a combination of three original ones. The first forces Paul to issue a warning against ‘evil workers, those who mutilate the flesh’ (3:2). This seems to refer to critics of Paul who were telling the Philippians that in order to become true Christians, they had to become Jews first, through accepting circumcision and other observances of the Jewish Law. This was the agenda that had dominated the Letter of Paul to the Galatians. It is as if the ‘false brethren who slipped in to spy on the freedom we have in Christ Jesus’ (Galatians 2:4) were now on their way to, or indeed had already arrived in, Philippi. The first argument that Paul had used against them in Galatians had been his own grace story (Galatians 1:13-24); he tells this story again in Philippians. ‘Whatever gains I had, these I have come to regard as loss because of Christ’ (3:7). He went on to sum up the teaching that dominates Galatians in a single verse: ‘that I may gain Christ. . . , not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but one that comes through faith in Christ’ (3:9). To seek salvation through any other way is to deny the value of the cross of Christ and to remove its offence (Galatians 5:11). It is to be earth bound and to refuse to live up to the heavenly call to be citizens of heaven (3:20). Proud though the Philippians might be to be citizens of Rome; their destiny was heavenly citizenship.

Another matter with which Paul had to deal in this letter, was to express gratitude for the support that he had received from the Philippians, in particular the gifts they had sent which he had received from Epaphroditus (4:18). When he wrote to the Thessalonians, he had proudly reported that because he had toiled night and day, he had never been any burden on them (1 Thessalonians 2:9). There is no such claim in this letter. These people, his ‘joy and his crown’ (4:1) had looked after him and his needs. His only duty was to thank them for it, and this he does towards the end of the letter when he informs them that no church had shared with him in giving and receiving as much as they had (4:15). In writing to the Corinthians, he again referred to the wealth of their generosity and their abundant joy despite their extreme poverty (2 Corinthians 8:2).

No treatment of Philippians can omit reference to this spirit of joy that pervades the letter. When the Church wants to stress the joy of its gospel message in mid-Advent, it is this letter that she quotes, ‘Rejoice in the Lord always; again I will say rejoice’ (4:4). This takes up a theme of the first paragraph of the letter, that Paul prays ‘with joy in every one of my prayers for all of you’ (1:4). And Paul can say all this despite his previous experience of Philippi which he writes of in the first of his letters: of how ‘he had suffered and been shamefully mistreated at Phillippi’ (1 Thessalonians 2:2). In the Acts of the Apostles, Luke reports the form this shameful treatment took, when he was beaten and thrown into jail, but this now all belongs to the past (Acts 16:19-34). Paul in this letter is ‘forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead’ (3:13).

Paul was confident that ‘the one who began a good work among you will bring it to completion by the day of Jesus Christ’ (1:6). Meanwhile, ‘whatever is honourable, whatever is just, whatever is pleasing. . . think about these things’, wrote Paul as he neared the end of the letter (4:9). In this Pauline year, inaugurated by Benedict XVI last June, may we rediscover this letter that Paul wrote from prison to his first converts in Europe. May its words constitute a pathway to Christ that many will tread and through them be led to a mature understanding and joyful acceptance of the gospel of Christ in our own day.

Peter Edmonds SJ is a tutor in biblical studies at Campion Hall, University of Oxford.